For a composer who was known in his day as the ‘the light of Spain in music’—to quote a memorable epithet coined by the music theorist Juan Bermudo (ca. 1510–ca. 1565)—it is surprising how little we know about Morales’s life, and how few of his works are regularly heard in concerts or in recordings. Yet it is exciting to see how recent research is shedding much needed new light upon the life and works of one of Spain’s greatest musical luminaries.

Morales composed a large amount of music—the vast majority Latin liturgical compositions—that were steadily issued during his lifetime from music presses in Lyon, Wittenberg, Nuremberg, Augsburg, Antwerp, Milan, Rome, and Venice. For at least fifty years after his death, demand for his music was so strong that publishers in Alcalá de Henares, Paris, and Seville joined this impressive roll call of international publishing centers. These numerous publications, as well as manuscript copies of his works, ensured an astonishingly wide international distribution of Morales’s oeuvre.

Morales composed a large amount of music—the vast majority Latin liturgical compositions—that were steadily issued during his lifetime from music presses in Lyon, Wittenberg, Nuremberg, Augsburg, Antwerp, Milan, Rome, and Venice. For at least fifty years after his death, demand for his music was so strong that publishers in Alcalá de Henares, Paris, and Seville joined this impressive roll call of international publishing centers. These numerous publications, as well as manuscript copies of his works, ensured an astonishingly wide international distribution of Morales’s oeuvre.

Although the international fame that Morales enjoyed throughout his lifetime resonated for centuries after his death, it is remarkable how little of his music is known today. Even the edition of his complete works remains incomplete, making the task of bringing his extraordinary works before the public a challenging undertaking for all but the most enterprising of performers. Similarly, our knowledge of Morales’s life remains disconcertingly incomplete. Nearly all of the information we have concerning the composer’s biography stems from research carried out in the 1940s and 1950s by José María Llorens Cisteró and Robert Stevenson. Until very recent research by Cristina Diego Pacheco, our knowledge of Morales’s life relied almost entirely on data that was extracted from archives over half a century ago.

There is no doubt that Morales was born in Seville, yet we know neither the date of his birth nor anything about his early musical training. We do know, however, that he was chapelmaster at Plasencia cathedral from 1527 to 1529 and that in 1535, on the same day that Pope Paul III commissioned Michelangelo to paint the wall of the Sistine chapel, he joined the Papal Choir in Rome as a singer.

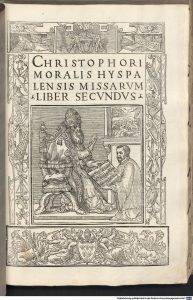

Whether or not Morales had been personally chosen for the Papal Choir by Pope Paul III, as the composer claimed in the dedication of his Missarum liber secundus (Rome: Dorico, 1544), it is clear that the musicians singing in the Papal chapel—composers like Jacques Arcadelt (1507?–1568) and Costanzo Festa (ca. 1485–1545)—enjoyed international renown. In addition to his French, Flemish, and Italian colleagues in the Papal chapel, Morales was able to count such accomplished Spanish composers as Bartolomé de Escobedo (ca. 1500–1563) and Pedro Ordoñez (ca. 1510–1585). It is his experience of such a lively cosmopolitan environment as Rome that places Morales’s musical development in a category quite separate from that of such other younger Spanish composers as Francisco Guerrero (1528–1599), Sebastián de Vivanco (ca. 1551–1622), Alonso Lobo (1555–1617), and Juan Navarro (ca. 1530–1580), to name but a few, whose entire careers took place within the peninsula. Indeed it was in Rome that Morales’s international reputation was established and consolidated.

Whether or not Morales had been personally chosen for the Papal Choir by Pope Paul III, as the composer claimed in the dedication of his Missarum liber secundus (Rome: Dorico, 1544), it is clear that the musicians singing in the Papal chapel—composers like Jacques Arcadelt (1507?–1568) and Costanzo Festa (ca. 1485–1545)—enjoyed international renown. In addition to his French, Flemish, and Italian colleagues in the Papal chapel, Morales was able to count such accomplished Spanish composers as Bartolomé de Escobedo (ca. 1500–1563) and Pedro Ordoñez (ca. 1510–1585). It is his experience of such a lively cosmopolitan environment as Rome that places Morales’s musical development in a category quite separate from that of such other younger Spanish composers as Francisco Guerrero (1528–1599), Sebastián de Vivanco (ca. 1551–1622), Alonso Lobo (1555–1617), and Juan Navarro (ca. 1530–1580), to name but a few, whose entire careers took place within the peninsula. Indeed it was in Rome that Morales’s international reputation was established and consolidated.

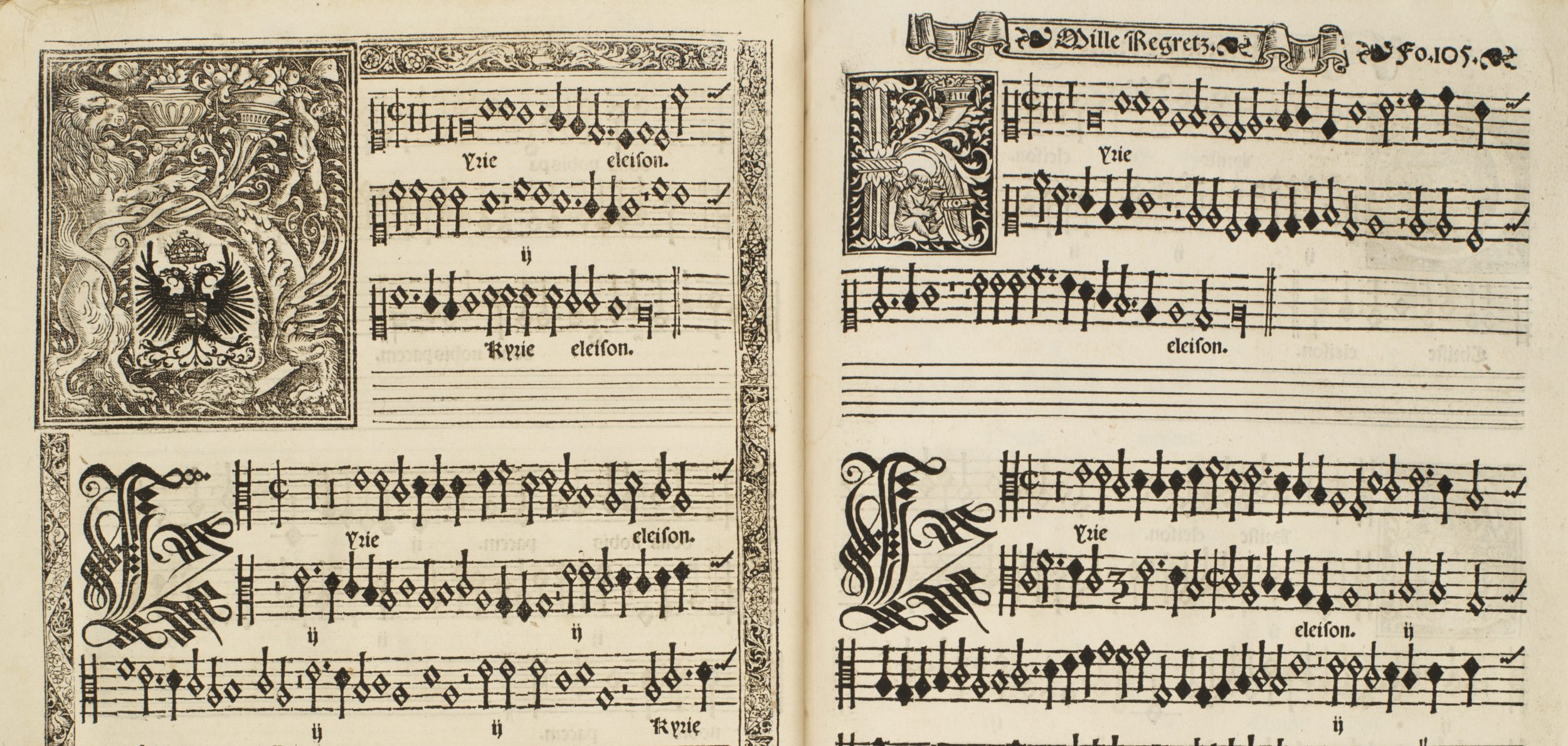

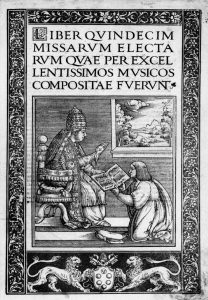

The year 1544 was one of enormous importance for Morales, for in this year he published no fewer than sixteen masses distributed over two books printed in Rome by the Dorico brothers, Valerio and Luigi. One of the many striking typographical features of Morales’s two mass books is the unabashed imitation of decorative features and page layout that appeared in a mass anthology published 28 years earlier: the Liber Quindecim Missarum (Rome: Andrea Antico, 1516). Whereas the opening illustration of the Liber Quindecim Missarum depicts a kneeling Antico presenting his book to Pope Leo X (illustration below), the corresponding page in Morales’s second book of masses shows Morales presenting his volume to Pope Paul III (illustration above).

Similar designs were to appear in such later Roman prints as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina’s Missarum liber primus (Rome: Dorico, 1554) and such later Spanish prints as Sebastián de Vivanco’s Liber Magnificarum (Salamanca: Artus Taberniel, 1607) and Juan Esquivel de Barahona’s Liber primus missarum (Antwerp: Artus Taberniel, 1608). Yet this was by no means the limit of Morales’s influence upon an entire generation of Spanish composers that followed him. Indeed, Morales’s motets were to provide a generation of composers with the richest musical yarn with which to weave their own masses.

Similar designs were to appear in such later Roman prints as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina’s Missarum liber primus (Rome: Dorico, 1554) and such later Spanish prints as Sebastián de Vivanco’s Liber Magnificarum (Salamanca: Artus Taberniel, 1607) and Juan Esquivel de Barahona’s Liber primus missarum (Antwerp: Artus Taberniel, 1608). Yet this was by no means the limit of Morales’s influence upon an entire generation of Spanish composers that followed him. Indeed, Morales’s motets were to provide a generation of composers with the richest musical yarn with which to weave their own masses.

One of the many remarkable features of Morales’s masses is that none was modeled on motets composed by Spanish composers. Instead, the Spaniard chose models written by Jean Mouton (1459?–1522), Jean Richafort (ca. 1480–ca. 1547), Philippe Verdelot (1470/80–before 1552), Nicolas Gombert (ca. 1495–ca. 1560), and Josquin Desprez (ca. 1440–1521). Morales was especially influenced by Josquin, and even the Spaniard’s masses based upon plainsong make frequent and sophisticated references to the great Franco-Flemish master. Yet it would be hasty to suggest that Morales’s love and knowledge of the music of the Franco-Flemish masters made him turn his back on his native Spain. For when it came to secular models, Morales based no fewer than three of his masses on the following Spanish melodies: Desilde al caballero, la Caça, and Tristezas me matan. The second of these, in addition, makes frequent reference to an ensalada by Mateo Flecha, La Caça.

The publication of no fewer than sixteen masses in one year demands to be recognized as a monumental achievement, yet it was Morales’s set of sixteen magnificats in all of the eight ecclesiastical tones that was to win him immediate, wide, and enduring popularity. In contrast, it seems astonishing to reflect upon the fact that, more than 400 years after Morales’s death, there is no complete recording of this set of splendid pieces—truly best sellers of their day. Some of the magnificats were reprinted more than ten times in the sixteenth century, and manuscript copies were distributed throughout the world. Early manuscript copies of the magnificats may still be found in such diverse locations as New York, Pastrana (Spain), Puebla (Mexico), Paris, London, Munich, Rome, Coimbra, Florence, Madrid, Rostock, Toledo, and Vienna.

The Morales Magnificats

Before examining Morales’s books of masses in more detail, we will take a moment to consider the composer’s magnificats. The compositional challenge posed by the magnificat, and indeed such a set of magnificats in each of the eight tones as Morales chose, differs significantly from the task of setting to music the Mass Ordinary. The magnificat is the canticle declaimed, in the first person, by the Virgin Mary as reported in the Gospel of St Luke (1:46–55) and the singing of the canticle forms the musical climax of the office of Vespers. The text has traditionally been broken into a series of ten brief verses analogous to psalm verses and for much of its history it has been sung to simple recitation formulae in much the same way as the psalms had been chanted. And just as the last verse of psalms was followed by the lesser doxology (‘Glory be to the Father…’), so too the final verse of the magnificat was followed by the same doxology. At Vespers, the magnificat would be preceded and followed by an antiphon. Precisely which antiphon was determined by the liturgical occasion and since antiphons were composed in one of the eight tones, a magnificat setting in the same tone as the antiphon was chosen. In fact the proper antiphons used for the majority of feasts and Sundays were composed in the first and second tones, yet Morales chose to compose magnificats in each of the eight tones.

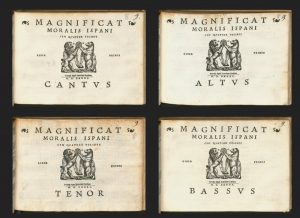

A time-honored custom dictated that the magnificat would be sung in alternatim, that is with either the even-numbered verses or the odd-numbered verses sung in polyphony; the remaining verses would be sung in plainsong to one of the magnificat tones. In the Papal chapel, however, in whose choir Morales had sung since 1535, the custom was to sing all twelve verses in polyphony. This is how the first few magnificat settings by Morales appeared when they were published in Venice in 1542. In later publications, however, Morales and his publishers seem to have catered for the alternatim practice that was universally observed outside of the Papal chapel. And that is exactly how the magnificats appeared in a publication that rolled off the presses of Antonio Gardano’s famous print workshop in Venice in 1545. Gardano’s 1545 publication appeared in the less expensive part-book format, in which each voice part appeared in its own booklet. Here we see how Gardano has arranged the even-numbered verses of Morales’s magnificat for four voices in the fourth tone.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

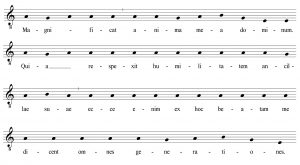

The plainsong verses 1 and 3, and Morales’s setting of verse 2, are given below in modern notation, figures 3 and 4.

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

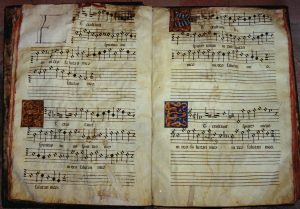

Despite the many advantages afforded by life in Rome, Morales decided, in 1545, to return to his native Spain, to take up the post of maestro de capilla in Toledo cathedral. In the following year, 1546, at Toledo cathedral, the scribe Martín Pérez copied this and other magnificats from Morales’s collection into a luxury parchment choirbook (E-Tc 34) that was decorated by the master illuminator Francisco de Buitrago. (See illustration.) We might imagine that Morales, on taking up the position of chapelmaster at the Spanish Primatial cathedral in Toledo in August 1545, had brought with him from Rome copies of his magnificats and that these copies provided the source from which Martín Pérez worked. In a 2013 visit to Toledo cathedral, the Ensemble Plus Ultra, directed by Michael Noone, and Schola Antiqua, directed by Juan Carlos Asensio, sang Morales’s Magnificat Quarti toni from the Toledo choirbook.

Until recently, it had been thought that Morales’s creative energy declined on his return to Spain, yet the recent discovery of fourteen previously unknown works in Toledan manuscripts demonstrates that on his return to Spain he was in fact at the height of his powers as a composer. In addition to the works composed by Morales at the height of his career, the Toledan manuscripts contain six hitherto unknown works by Francisco Guerrero, works that were written during the teenager’s apprenticeship with Morales in Toledo. Not only are these the earliest works of Guerrero that we possess, but they also reveal the unmistakable guiding hand of his mentor, Morales.

It is difficult to underestimate the importance of Guerrero’s period of study with Morales for the history of Spanish music. After ten years serving in the Papal chapel, Morales returned to Spain to take up a position at the head of music at the Spanish Primatial cathedral, and there he was soon visited by an unknown but highly talented teenager from Seville who was destined to become one of the greatest composers of the following generation. How appropriate then, that it was Francisco Guerrero—and no other composer—that Tomás Luis de Victoria (ca. 1548–1611) chose to honor when in his Roman Motecta Festorum (1585) volume he published two of Guerrero’s motets alongside his own works. Victoria, of course, was thoroughly familiar with Morales’s works, choosing to base his Missa Gaudeamus upon the splendid motet Jubilate Deo omnis terra that the older composer had written for the peace treaty of Nice in 1538.

Despite his acknowledged preeminence in both his own time, and ours, Morales’s wonderful music remains largely unheard. It is time to rediscover this remarkable genius with our own ears. It is time for scholars to enter the archives and libraries in order to clarify those many aspects of Morales’s life and works that remain in the shadows. Once his works are published in modern editions of the highest quality, then the music can be brought to life for us all.