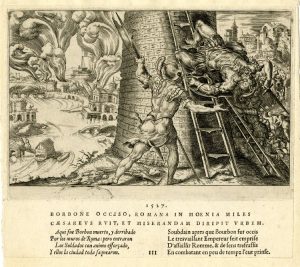

The second mass in Morales’s first book is a mass based upon, and named after, a motet by his older contemporary Nicolas Gombert (ca.1495–ca.1560). Gombert probably composed his motet Aspice Domine in the late 1520s and his choice of text, and the deeply penitential mood of the music, are thought to be, at least in part, his creative response to one of the notable war atrocities of that era, the sack of Rome in 1527.

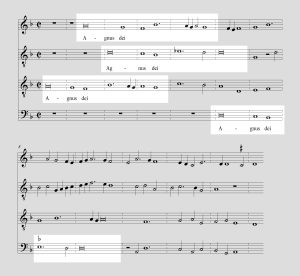

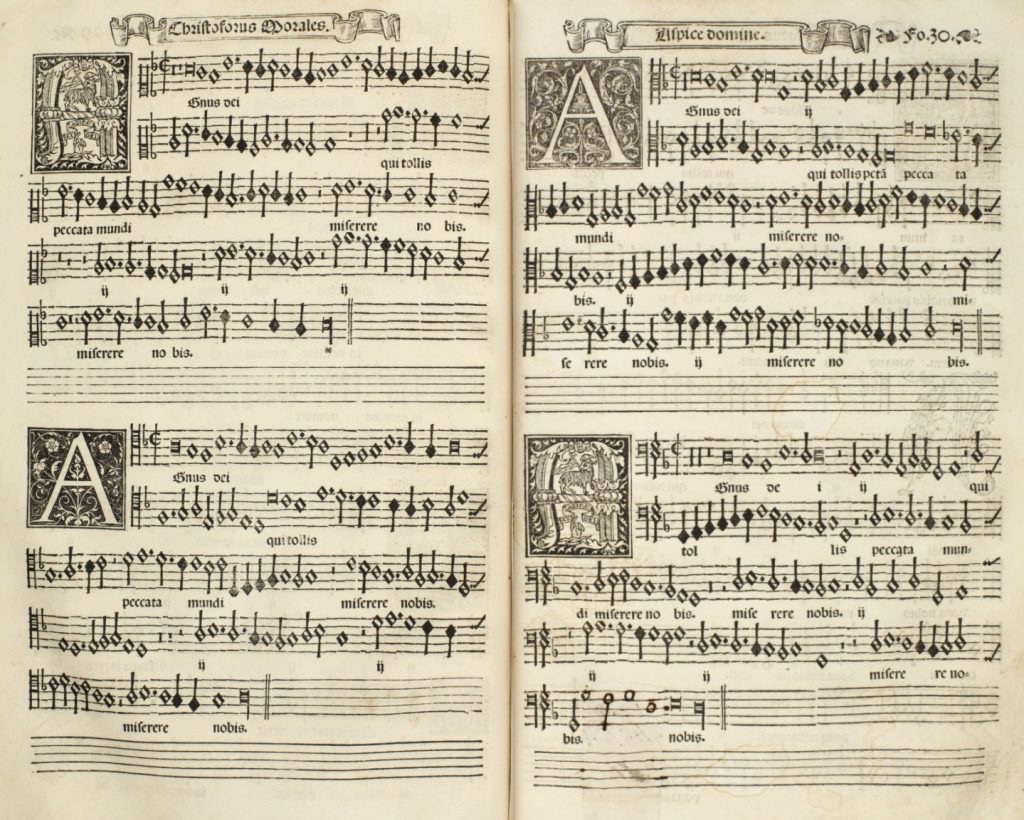

The following video, recorded in the Burns Library, shows four singers from the Ensemble Plus Ultra singing the Agnus Dei I (illustrated below) from Morales’s Missa Aspice Domine from the John J. Burns Library copy of Morales’s 1546 book.

An English translation of the Latin text of the first half of Gombert’s motet follows:

Behold O Lord, the city that was full of riches is made desolate,

she that lorded it over the nations now sits in sorrow:

and there is none to console her, except you, our God.

Entirely by coincidence, Gombert’s motet was first published in Lyon, in 1532, by none other than Jacques Moderne, in the first book of his popular motet anthology, Motteti del fiore.

As was the case with his pirated Morales mass book, it is unlikely that any of the composers represented in this 1532 motet volume knew in advance that Moderne was printing their music, and the idea that the printer might offer payment in lieu of royalties would never have occurred to them. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that, in most cases, their reputations were enhanced by having their music circulating in print. Morales was probably still in Spain at the time Moderne’s book first appeared, and he may well have first encountered Gombert’s motet in its pages. If not, Morales probably heard and sang it a few years later, after he himself moved to Rome to take up a post as a singer in the Papal choir in 1535.

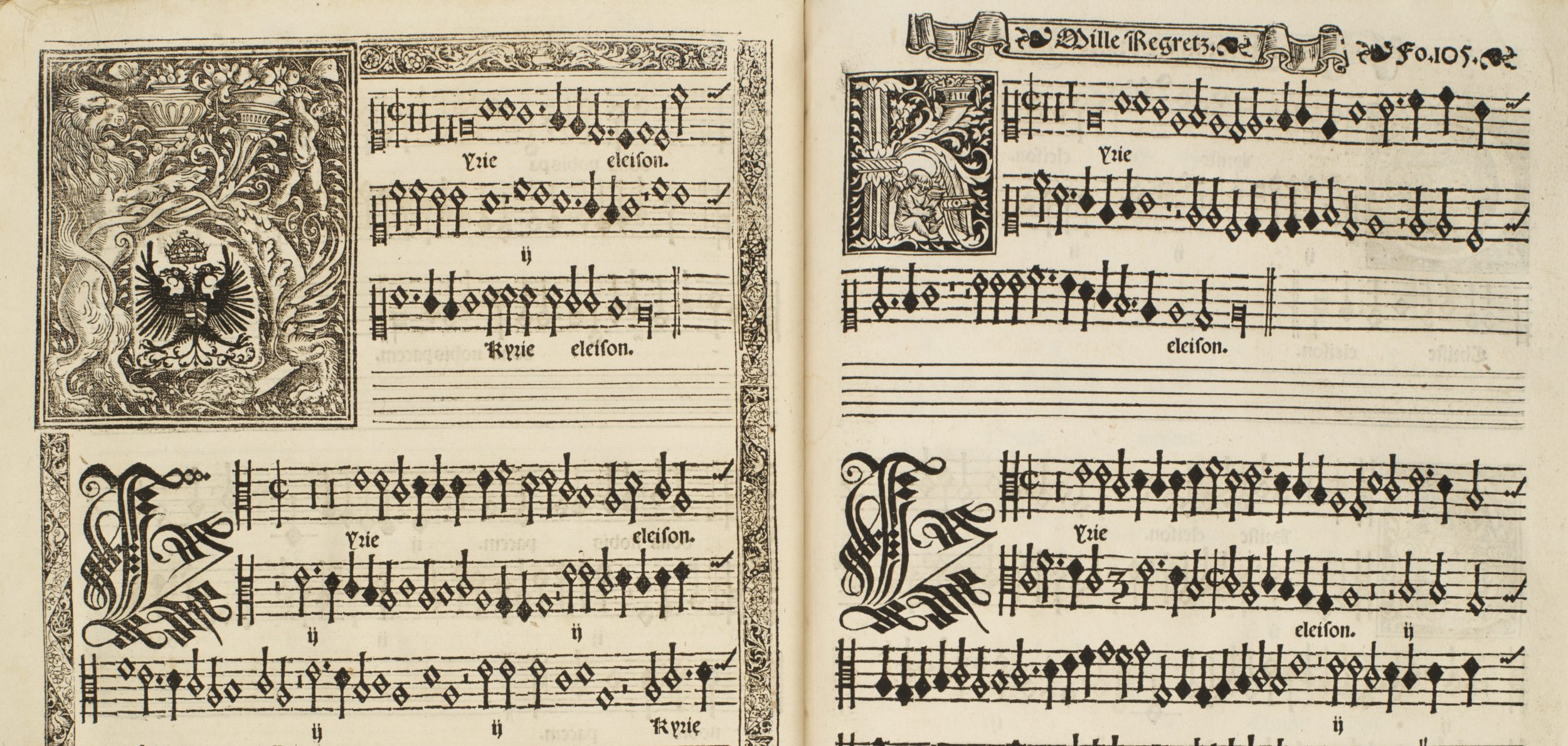

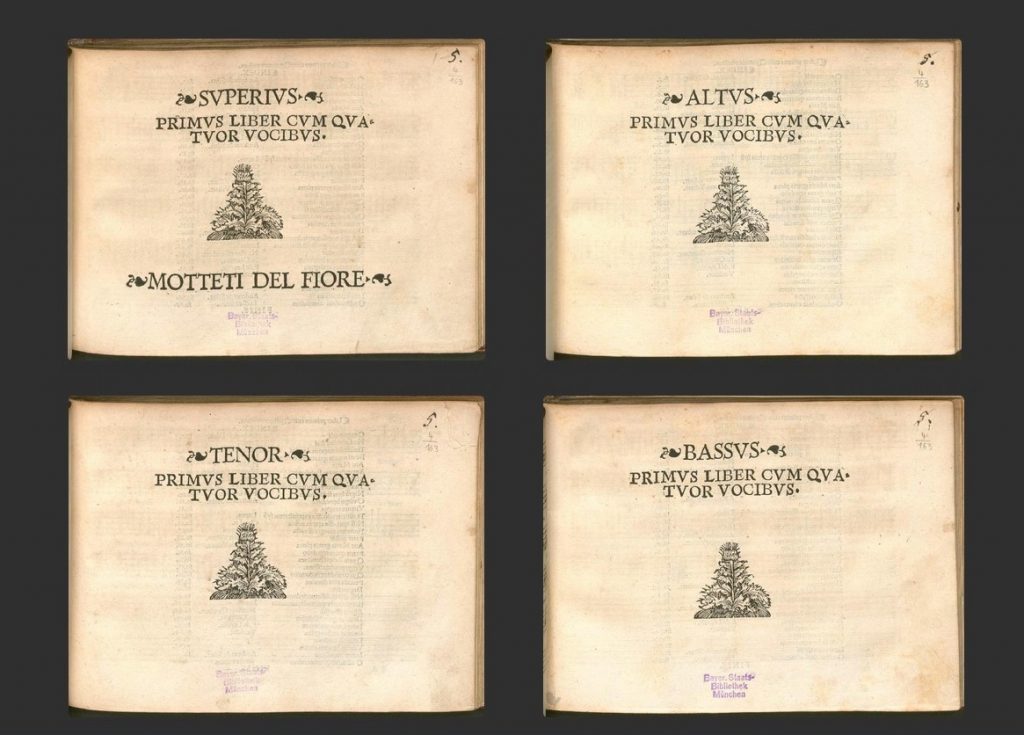

Moderne’s Motteti de fiore was not printed in a single book – in the same large format choirbook layout as his Morales mass volume – but as a set of four small format partbooks. In sets of partbooks, the music for each separate voice is printed in its own dedicated book, each small and portable enough for singers to hold their own copy, rather than them having to gather around a large and heavy choirbook resting on a lectern.

In presenting its digitized copy of the original 1532 Moderne book, the Bavarian State Library has helpfully arranged the four separate partbooks in a single screen. The following images (Figures 1 and 2) are screenshots showing, first, the title pages of all four partbooks, and, second, the opening of Gombert’s motet.

The opening of the Agnus Dei I of Morales’s mass is closely patterned on the opening measures of Gombert’s motet. Morales retains both the four-voice texture and the minor mode tonality of Gombert’s original. He also faithfully copies Gombert’s opening melodic figure, though leaves his own imprint upon the music by altering the order and timing of the entry of voices.

Gombert’s motet begins with the soprano, followed by widely spaced successive entries for the alto, tenor, and bass, and a repetition of the opening figure by the alto (Figure 3). This sort of regular and spacious layout of voices is, of course, similar to the opening or exposition section of a formal fugue of a later era.

- Figure 3

Morales, however, starts with the tenor, with the soprano and alto joining in in quick succession (Figure 4), so that the voices sing their different versions of the same figure simultaneously. Once Morales has represented Gombert’s opening point of imitation in all four voices, however, he leaves his model behind, and completes the opening episode in his own characteristically sinuous polyphony.

- Figure 4

![Gombert’s motet Aspice domine, from Motteti del fiore, primus liber cum quatuor vocibus (Lyon: Jacques Moderne, 1532), folio [page] 48 of each of the 4 partbooks.](https://moralesmassbook.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GOMBERT-Aspice-Moderne-1532-Aspice-1024x762.jpg)